ABOUT THE PLANTATION COMMUNITIES IN SRI LANKA AND THEIR MAJOR ISSUES

PLANTATION COMMUNITY IN SRI LANKA

AND THEIR MAJOR ISSUES

ABOUT THE PLANTATION COMMUNITY

The

Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka formerly known as Ceylon is a pear

shaped tiny island located in the Indian Ocean about twenty eight kilometers

off the South-eastern coast of India. Sri Lanka has a population of about

twenty one million in which Sinhalese makes up seventy four percent of the

population and are concentrated in the densely populated Southwest. Sri Lankan

Tamils, whose South Indian ancestors have lived on the island for several centuries, are

about twelve percent of the total population live who throughout the country

and predominantly present in the Northern Province of the island. Indian

Tamils, a distinct ethnic group, also known as plantation Tamils represent

about five percent of the population. The British brought them to Sri Lanka in

the nineteenth century as estate laborers to work initially in a coffee

plantation and then later in tea, rubber plantations. They remain concentrated

in the "tea country" of South-central Sri Lanka.

The

labour law in Sri Lanka was discussed in 1840s during the British colonial

period where was the coffee plants had been destroyed by an unidentified fungus

and it was replaced with tea as a commercial crop in 1867 by Mr. James Tailor,

whom was the citizen of Scotland and succeed in planting tea instead of coffee

and his first tea production was marketed in Sri Lanka in 1872 at Kandy city.

As

follow the other land owners also started to plant tea by replaced the coffee

in a bigger scale. Tea production was

developed as biggest economic market in Sri Lanka in 1890s. The labour shortage was raised up as a major

issue to meet the demand, and the local manpower was inefficient to meet and

fulfil the demand and supply at that time.

So they decided to bring labour from south India by introduce the system

of ‘Tundus’ which was used as visa to enter into the country for employment and

‘Kanganies’ (Agent) the name of the person who had contact to bring labours

from south India was given the Tundus to supply labours. There were number of people had come from

south India and travel (by foot) from the north part to the central part of Sri

Lanka and while walking there are number of people who died due to fever and

dearie. All of them recruited as

labour and they were provided with a small house call line rooms and they were

supplied with basic food, cloths, bed sheets etc. And treated as slaveries by

the owners and only expected to take maximum output a day.

The

contacts for hire and service ordinance No. 5 of 1841 was introduce as first

ordinance for Labour Law in Sri Lanka based on hiring contract labour for the

said Plantations. Under this ordinance

the ‘Kanganies’ had authority to bring labour from India and supplied to the

British Plantation owners. The labours

those who had brought are employed as Male for cleaning, planting, manuring and

Female was used especially for plucking.

The working hour was nearly 12 and the female had to work for 12 hours

and Male for 08 hours.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS OF THE

PLANTATION COMMUNITY IN CENTRAL PROVINCE

The

bulk of the Indian Tamil plantation workers in Sri Lanka were drawn from the

most depressed and lowest caste groups in South India. While this may be an artefact

of great poverty among such groups at the time when the colonial masters were

recruiting such laborers from 1840s, onwards, it appears that the colonial

masters and the employers of such laborers were deliberately looking for those

from the relevant caste groups in their search for a pliant work force due to

their firm stereotypical views about race and caste of workers.

Over

seventy five per cent of the Indian Tamil workers represent the lowest levels

in the South Indian caste hierarchy, but interestingly those in supervisory

grades were selected from among the higher status. Even though opting the

plantation work force would have produced a levelling influence on people from

different caste backgrounds, this has not happened for over hundred and fifty

years. The colonial system and the plantations imposed many restrictions on the

Indian Tamil plantation workers in order to keep them under harsh living

conditions and minimum worker benefits within the plantation workforce.

The

Sinhala and, to some extent, Tamil nationalists movements in Sri Lanka treated

them as an immigrant group with no local roots and mere interlopers brought in

by the colonial masters. As an ethnic minority in post-independence Sri Lanka,

the Indian Tamils lost their citizenship rights and a pro-gram me for

repatriation to send a significant number of them back to India was initiated

in the 1960s. One could argue that the “Untouchables” became “Touchable” within

the plantation economy as members of lower castes worked and lived side by side

with higher caste people within the plantations. There was however some degree

replication of caste or even “an invention of caste” within the plantation

economy as workers hierarchy broadly conformed to the caste system and some

services such as sanitary work, washing of cloths etc. were extracted on the

caste basis. However at present most of the population in estates engaged

working in estates

EDUCATION AND RELATED ISSUES OF

THE PLANTATION COMMUNITY

Education

is the main factor that determines the social status of a development process

of an individual as well as a community. It transforms people psychologically,

socially and culturally. The plantation community is one of the marginalized

groups that are more vulnerable in educational achievements. Due to the poor

education facilities and lack of qualified teachers students have to depend on

private tuition classes due to the poor financial situations at home it is very

hard to find t fees to the tuition classes and the students are discouraged to

follow the higher education.

The

comparison of literacy rates with national level showed that the plantation

community was only 76.9% while the national average was 92.4%. Similarly, only

20.2% of the plantation population has a secondary education and only 2.1% of

them had a post-secondary education. The comparable figures for the all island

are 52.2 and 20.7% respectively. More than half (55.9%) of the plantation

population had only primary education. A few of them had entered into the

university system (Treasures of the Education System in Sri Lanka, 2005).

The

state of public education was outlined in a report by the Sahaya Foundation, a

non-governmental group, in 2007: “Statistics indicate that of the school age

children in the plantation sector, only 58 percent attend up to completion of

primary schooling and only 7 percent of students who pass Ordinary Level (10th

grade) proceed to Advanced level studies. Less than 1 percent of the students

who complete their Advanced Level Exam actually make it to university (less

than ten a year).”

The

report continued: “Reasons for the dropout rate are a culmination of extreme

poverty, lack of awareness as to the importance of education, and lack of

parental motivation. Furthermore, the schools in question do not have

sufficient resources to ensure attendance.”

According

to a 2007 World Bank assessment, the country’s official literacy rate in

2003-2004 was 92.5 percent, but for the plantation sector was 81.3 percent. In

the case of women, the island-wide literacy rate was 90.6 percent, but was 74.7

percent for the plantation sector.

The

dropout rate for the estate sector is high—averaging 18% percent at grade five

as compared to just 1.4 percent for the whole country. According to education

ministry data, the male transition rate from primary to secondary level in the Numara

Eliya district is far lower than other districts. Many boys are compelled to

join the workforce.

Public

schools throughout the country, including in Colombo, are poorly

resourced—lacking qualified teachers, science laboratories, proper buildings

and playgrounds. But the conditions facing students in Colombo and the plantation

districts are worlds apart.

There

is an acute lack of teachers in the estate areas. According to 2007 records,

the student-to teacher-ratio was 1:45 as compared to 1:22 for the island as a

whole. This translates into far larger class sizes, cramped conditions and

overworked teachers.

Proposed intervention-

as mentioned above Education is the main factor that determines the social

status of a development process of an individual as well as a community. It

transforms people psychologically, socially and culturally it the responsibility

of everyone to educate the society which will empower everyone individually and

collectively for an example providing IT/Technical Knowledge.

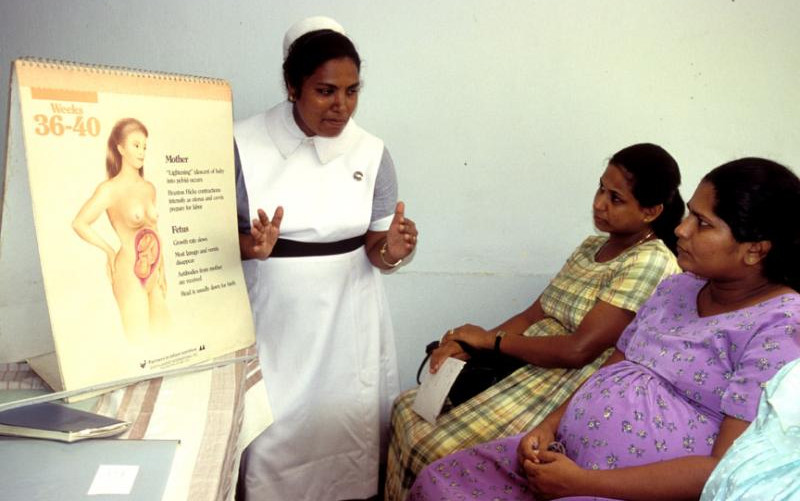

HEALTH RELATED ISSUES OF THE

PLANTATION COMMUNITY IN CENTRAL PROVINCE

The

indicators of health and nutrition are another source which reflects the

backward and neglected nature of the plantation community. The percentage of

undernourished children below the age group of five years in the plantation

sector was 38.9% whereas the percentage of the rural and the urban sector were

lower and they were 21.8 and 12.8% respectively. Infant mortality in the sector

was 60.6% while the national rate was only 25.3% and still birth rate is 20% in

the plantation sector.

The

plantation health sector is still not integrated with the national health

stream and it is treated as a separate entity. As a result, national health

policies and health programmes are not fully covering the plantation community.

Plantation

human development trust (PHDT) is

the institution handling the entire health services of the plantation sector.

Estate hospitals are not equipped with

the

necessary facilities. Lack of qualified doctors, qualified health staffs and

lack of medicine, indoor treatment facilities are the major problems faced by

the estate health service.

Proposed

intervention- Producing more doctors so that they can provide basic medical

Facilities in low cost and pressuring governmental and non-governmental

organizations to build hospitals in the local area.

HOUSING, WATER SUPPLY AND

SANITATION RELATED ISSUES

The

plantation sector has its own identical housing patterns known as line rooms,

introduced by the colonial planters. The line rooms are barrack type structured

with two hundred sq. feet for an entire family, with hardly any ventilation, no

privacy for grown-up children & women. yet overcrowding due to larger

families with their dependent parents. In the plantation sector, 185,533

families consists the population of 777,730 who lives in 163,580 housing

units/line rooms.

Most

of these line rooms are more than100 years old and seventy percent of them

lives in dilapidated conditions. The percentage of self-owned houses among the

plantation community is estimated to be low as 10.2 and others who live in the

line rooms owned by the plantation companies. Nearly, 1families do not have even line rooms they live in

temporary huts.

However,

as a result of various housing programmes implemented by the different

organization 45,000 new housing units were constructed and some of the old line

rooms were upgraded. However, given the large number of unsuitable housing

units in the plantation sector the challenges behind the provision of decent

houses for the plantation community is enormous. With regard to the provision

of drinking water and sanitation 90 and 62% of the needs of the estate sector

are met respectively due to Donors, NGOs and Government interventions.

But

still 74% of the estate households use common taps and 15.5% use common well

for drinking water. While nearly 25%of the households use latrines, another 25%

do not have access to latrine facilities. After the re-privatization in 1992.Government

Agencies and NGOs had interest to improve the water supply and sanitation

conditions, but the problem still prevails in higher level compare to the other

sectors (Status of Workers Housing in Plantations, 2004).

Proposed

intervention: Empowering the families to have own house and facilities and

pressuring government for own lands and basic infrastructures.

Employment related

Issues:

Labour

force participation rate in the estate sector is around 45%. The sector also

characterized by high labour force participation rate (43.4 percent) among

females compare to the other sectors. However, in the recent years the labour

force participation rate of the sector is decreasing due to the emerging trend

of greater emphasis on education over employment at a relatively younger

generation. However there is a decline in the participation of female in labour

force from 47.6% in 1986/87 to 45% in 1996/97 in the plantation sector.

Out

of the total active persons in the plantation community 80.6% are employed

while the unemployment rate is 19% overall. But the unemployment rate among the

younger generation is 70.5%. While 7.5% of the working people have permanent

employment the others which are 28.7 percent are temporarily employed and 3.1%

are self-employed.

On

the other hand, only 9.1% of the plantation people have subsidiary occupations.

Unemployment is an acute socio- economic as well as development problem because

of its relationship to the poverty and human development.

Unemployment

has been identified as an emerging problem among the plantation youth

especially after privatization of the plantations in 1992. Among all the

plantation youth, the unemployment rate is 38.63% but it is 50.6% among the

educated youth. Of the working youth only 43.67% have permanent employment and

the balance engaged in temporary or casual works (Labor Force.

It

is also noteworthy to explain that among the working youth only twenty five are

satisfied with their present jobs while 67.75% are not satisfied. The reasons

for dis- satisfaction are low wage, lack of incentives, low states of job, lack

of promotional aspects, lack of social security benefits etc. The higher

poverty line defined by the Department of Census and Statistics revealed that

nearly 80% of the plantation households lie below the poverty line. The income

of plantation workers household is determined mainly by five sectors such as

daily wage rate which is determine by the collective agreement, the number of

days of work offered to them by the estate management, the number of days they

actually worked, non-plantation work income that they are able to earn and

number of income receives in the household. From the inception of the

plantations, the managements have maintained a low wage mechanism in order to

ensure chief labor and higher profit. Because of this mechanism, they receive

very low level of wage in the country compare to the workers in the other sectors.

The current salary of an estate worker is Rs1000.00. which is very low to

manage with the current economic crisis in Sri Lanka.

Proposed Intervention: with

the support of the government and non-government organizations support creating

more job opportunities and self-employments for men and women for a sustainable

development.

CHILD PROTECTION AND CHILD LABOUR

RELATED ISSUES

Although

there is a slight improvement in schooling among the plantation children, child

labor and child protection bound to be one of the serious issues. A study

conducted by Vijesandiran for centre on plantation study showed that among the

plantation children below eighteen years old, 28.82% had engaged in child

labour. The child labour rate is high among the female (33.55%) compare to the

male children (22.58%). Poverty and poor education facilities are found to be

the major causes of child labour problem. It is observed that parents are

compelled to send their children to work as avenue to cope with poverty

incidence.

Due

to the poverty issues in families most of the children effected by

Malnutrition, mothers have to go to estates for work and children are looked

after at the day care centers. A child doesn’t get a mothers love during the

child hood at the day care centers in some places children are mostly communicated

and taught by not in their mother tongue

and they get the pre school education in their second language and this

effects in their pre schools and making the student a slow learner. There is a

high demand of well-trained preschool teachers who can teach in their mother

tongue.

Proposed Intervention: Creating

Child care centers with all the basic arrangements so that a child can grow

happily which will fit their future needs.

ALCOHOLISM /GAMBLING/DRUGS/SUICIDE

AND YOUTH RELATED ISSUES

In

addition to this, it is also observed that there is an increasing trend in

alcohol habit among the members of the plantation community. There is nearly

60% of the plantation workers consume alcohol and they spend 6.6% of their

total income on alcohol and 6.7% of their income on Tobacco and Beetle.

Alcoholism is seen as two aspects in relation to poverty in the plantation

community (Household Income and Expenditure Survey, 2003). One is that the

alcoholism is one of the major causes for higher poverty incidence and the

other one is that it is the result of the higher level of human poverty which

prevails in the community. In 2002, 53 years after independence from the

British and more than fifteen years after the large privately owned tea

plantations were declared as state corporations and again after the 1995/96

privatization of plantations, female wage earnings continued to be handed over

to the males.

This

effectively carries on historically established norms of gender discrimination.

Management personnel confirmed earlier observations that frequent family

conflicts arise because men tends to waste the wages of their wives or other

females on alcohol and gambling.

And

it has been a major problem with the youth of the central province is taking

drugs which leads to dropping out from schools and wasting time without

engaging any employments. Yet there is an increment of crimes and robberies

murders, suicides etc.. It is very important to keep

Proposed

intervention: every

youth engaged in activities which will benefit them individually as well as

collectively such as engaging in skill development through using digital literacy.

Status of

Women and related issues: Sri Lanka has attracted much

attention as a country in which women are unusually favorable in society and in

political field when compared to other countries of the SAARC region but the

plantation women have been neglected and marginalized by development programs.

Plantation women’s work has been undervalued and underestimated.

The

economic contribution to women has not been fully recognized. The plantation woman

tends to have multiple roles. Women have double burden as income earners and as

care-takers. As a result, they do not have leisure time on a normal working

day. Estate women are vulnerable to the oppressive economic and social

structures which exist in the system that has continued to be their subordinate

for over a century.

Women’s

subordination is rooted in patriarchy, in the plantation families, decision

making on major issues like education of children, their employment and

marriage, handling of the household authority structure of the family is been

decided by the husband. Women form the majority among trade union subscribers

but not even 1% of the position in the decision making level is shared by them.

The isolated life led by them in the estate is another issues, most of them do

not know any world beyond their estate. Female literacy rate remain lower in

plantation sector than in the other sector and the school dropout rate of

females remains high. It has been recorded that only 53% of female children

actually complete primary schooling, 24% attends secondary school and only 4%

remain until GCE ‘O’ level.

Women

working as tea pluckers form the single largest segment of the plantation

workforce in Sri Lanka. The smooth operation of factory-based tea processing is

heavily dependent on the skillfulness and efficiency of the tea pluckers who

brings in the green tea leaf. The female workers are economically far more

important than male workers. Until 1978, however, female laborers were paid 20%

less than male laborers. In 1978 the government passed legislation to increase

and equalize plantation wages for all labor categories, thus removing the wage

anomaly between male and female plantation labor that had existed in the sector

since its beginning in the mid- nineteenth century.

According

to the office records of plantations, female workers earn relatively higher

incomes than men, but evidence suggests that they neither handle nor manage

their earnings. To start with, the female workers do not collect their own

wages. Women's wages are routinely handed over to the males (husbands/ fathers)

by the management and this practice was originated in the mid nineteenth

century, when the Indian Tamil labor gangs, consisting entirely of families

were brought to the newly opened plantations in the island from southern India.

In

2002, 53 years after independence from the British and more than fifteen years

after the large privately owned tea plantations were declared as state

corporations and again after the 1995/96 privatization of plantations, female

wage earnings continued to be handed over to the males.

This

effectively carries on historically established norms of gender discrimination.

Management personnel confirmed earlier observations that frequent family

conflicts arise because men tends to waste the wages of their wives or other

females on alcohol and gambling.

In

the view of management, however, women do have the opportunity to collect their

own wages, since there is a compulsory work stoppage when wage payments are

made. Plantation workers are paid twice a month and although there is a work

stoppage on the formal payday, the vast majority of the women tea pluckers

simply stay at home and male members of the household collect their wages. It

should be noted however, that there are instances when women collect the men's

wages as well. But such cases are extremely rare.

On

the days when ‘wage advance’ is paid, only a few plantations stopped work

anyway, usually in the afternoon, when the men were relatively free (Samarasinghe,

1993). It may be argued that as a consequence of a long history of male control

of their earnings, the Indian Tamil female tea plantation workers would have internalized

the belief that they cannot manage money and voluntarily leave the management

of their earnings to the males.

But

this does not appear to be the reality. For instance, they have small amount of

money that they had managed to hide away in an informal savings system called Ceettu.

The participants would take turns in receiving the pooled sum of money each

month. That money is not given to the males and the women spend it mainly on

purchase of household goods and in some instances on jewelry. As for collecting

their own wages, they had neither the resources nor the organizational

capability to change the pattern in the face of a male-dominant workplace and a

patriarchal domestic sphere.

They

viewed themselves as producers, working as many hours as possible to earn the

maximum wages.

In

addition to the above characteristics and social realities, tea plantation

workers devote their lifetime which to an outsider may seem irrational. This

situation of total institution remains almost the same as it was in the colonial

period. It is the males in the family who collected the cash payment and spends

it on themselves.

Most

of the families especially females in the household suffer and have to bear

burdens mentally and physically with huge responsibility and worries in their

lives. They have to earn, prepare meals, look-after the family, arrange

marriages and dowries for their female children, look after grandchildren and

the like. They tolerate all sorts of

Harassment

from their drunken males. As a family they have a peculiar lifestyle, which is

totally different from that in the surrounding village culture. Culturally and

socially females in Sri Lankan society still behaves in a traditional manner.

This includes not drinking alcohol, smoking, or grumbling except for some elite

classes and westernized females (Samarasinghe, 1993)

Proposed

intervention- Empowering women economically and politically solve many problems

of women it is our responsibility to supporting the women for empowerment.